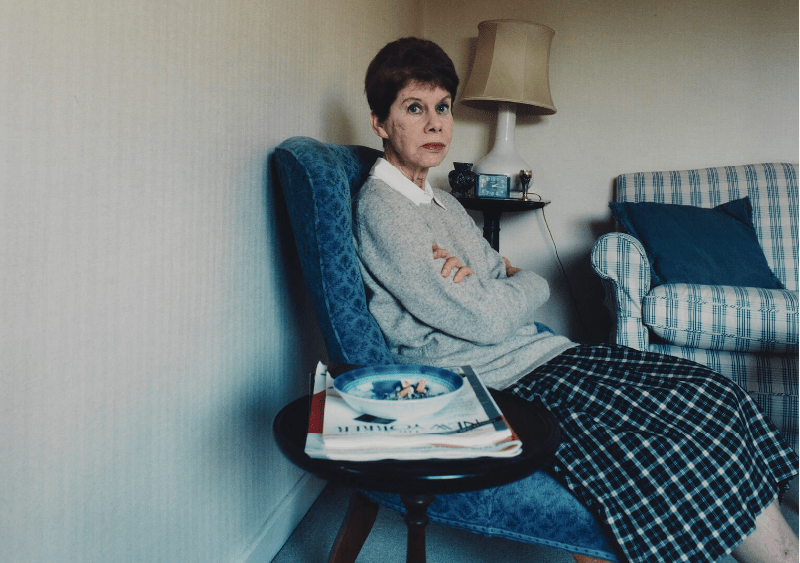

“People feel at home with low moral standards.”

That’s a quotation from Hotel du Lac, a 1984 novel by Anita Brookner, an author whose works feature kind and gentle protagonists losing out on life’s prizes to bolder and more morally questionable characters. Thematically, her writing is like Kazuo Ishiguro’s in that it portrays characters who realise they’ve not made the most of life and accept it’s too late to change anything.

Given her plots, it’s funny that Brookner was a prolific reader of Dickens, an author in whose works morality reigns and kindness is rewarded.

The power-hungry schemers in Dickens’s novels are punished – Miss Havisham burns to death, Ralph Nickleby hangs himself, Uriah Heep gets arrested; the list goes on. Conversely, the principled protagonists overcome their trials and gain happiness.

But Brookner wrote life differently, presented a less just world to readers, one that’s more loyal to our experiences of reality. More than that, she showed us the ugliness that morality often hides.

“… the terror behind all of these things”

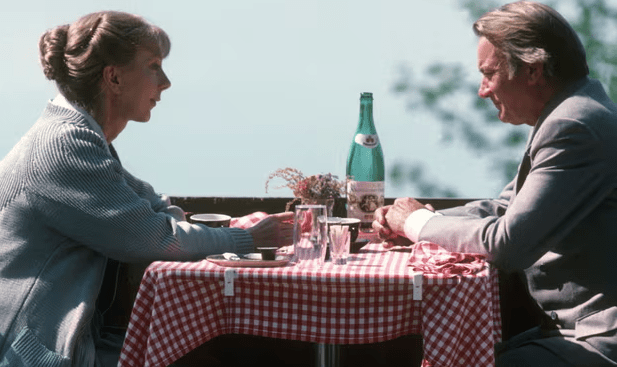

In her 1983 novel, Look at Me, Brookner’s narrator, a shy librarian, grows obsessed with a couple she befriends, who are beautiful, selfish, capricious. She views them as God-like figures, as their wealth and looks grant them a charm and a hold over others, herself included. Romantic figures, they behave as they please, and eventually discard her.

In one scene, the protagonist walks in on them lazing on their sofa in the middle of the day, eating expensive chocolates and dropping the wrappers around them. In ugly people, we find this slothful behaviour repugnant; in the physically appealing we allow it.

While the protagonist is drawn to these attractive, thoughtless characters, she simultaneously asserts a loathing for those (like her) who exhibit common decency:

“… that reliance on old patterns, that fidelity, that constancy, and the terror behind all of these things… No more.”

What is the terror behind these noble attributes like fidelity and constancy?

Brookner’s narrator doesn’t say explicitly, but I think it’s a simple terror of death. People, including me, behave within certain moral parameters from a fear of losing their possessions. The exposure of infidelity and inconstancy can snowball into a loss of financial stability and reputation.

When someone shows high moral standards, you can interpret their behaviour as you wish: perhaps as a sign of an admirable discipline, one acquired from diligent study and countless nights of soul-searching; or, perhaps, as a sign of a slavish, fear-inspired adherence to a mass-disseminated popular doctrine, ancient or modern, one that’s prolific in the community in which that person was raised.

Who are the people craving consolation?

In Brookner’s fictional world, moral characters are dull, comparatively unattractive, behaving respectably in anticipation of reward, or from fear of rejection. The shameless and self-assured characters captivate their audiences through their risk-taking and rejection of decency, claim everyone and everything as their rightful inheritance, and leave in their wake the novels’ protagonists to reflect that their own measured approach to life reaps a pitiful and unenviable existence.

That’s not how most stories end.

Brookner’s narrator explains why in Hotel du Lac:

“Aesop was writing for the tortoise market. Axiomatically, hares have no time to read. They are too busy winning the game. The propaganda goes all the other way, but only because it is the tortoise who is in need of consolation. Like the meek who are going to inherit the earth”

Many people don’t want stories where selfish characters, born lucky with things like money and beauty, secure a stream of near endless excitement and fulfilment – they know that’s the way things are anyway and they’d rather experience a fantasy where such people are clawed down to the gutter, and where a member of the suffering masses is elevated onto a pedestal they deserve.

It’s nice to think that there’s a prize waiting somewhere on the horizon if we continue to sit on the side-lines and play fairly.

Most of the art and media we consume is designed to act as a painkiller, to console those who believe themselves wronged. Brave artists, like Brookner, refuse to do this, and administer further pain instead, in the name of honesty.

Leave a comment