I think most people, given the choice, would prefer to have their lives celebrated, rather than tolerated. “The way you live is fantastic” sounds more validating than “I respect your right to exist”, though I’m happy enough with the latter. Perhaps I have low expectations of others.

There’s a minor episode in British politics relating to this theme that I sometimes think about. It concerns Tim Farron’s 2015-2017 leadership of the Liberal Democrats, and the conflict between his personal and professional beliefs.

Revealing your Soul

In 2015, Farron was (as he remains today) a devout Christian in a political party known for its support of gay rights. He had voted in favour of same-sex marriage in 2013, but his overall record on issues surrounding sexual minorities was patchy and inconsistent. It suggested an inner conflict.

When he ascended to party leadership, an interviewer from Channel 4 asked his opinion on gay sex. He answered that his personal views weren’t important and intimated a difference between his politics and his faith. The problem was that this rendered him inauthentic.

The issue reappeared in subsequent interviews, and he faced opposition within his own party. Upon stepping down in 2017, he admitted that he had become “torn between living as a faithful Christian and serving as a political leader”.

I found the whole thing quite strange, because surely his innermost thoughts and feelings didn’t really matter, did they? What mattered were the policies he was promoting.

On a personal level, I’m confident that Farron and I have almost nothing in common, but I also think the world would be kinder if more people like him were in charge.

The longer I live, the more I lean towards believing it’s unrealistic to expect us all to celebrate each other. To celebrate means to honour and to praise. It’s a big ask.

I’m not sure it’s even possible to simultaneously celebrate every single marker of identity – too many of them oppose each other for this to be feasible. Tolerance is a bit of an outmoded term, but it seems a noble enough goal.

Troubling and strange

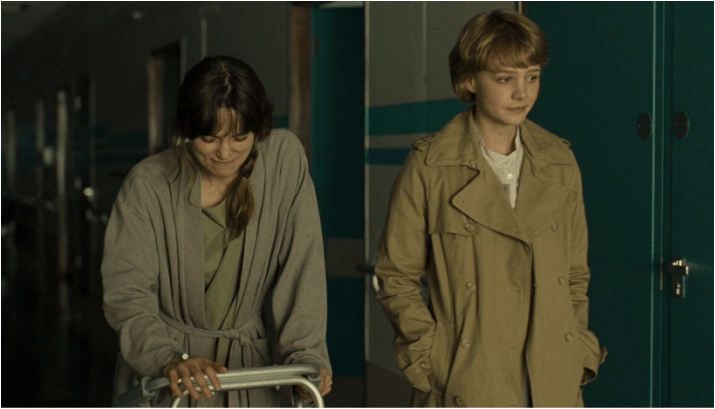

In Kazuo Ishiguro’s dystopian novel Never Let Me Go, there’s a scene where the narrator Kathy, a clone created for organ donation, talks about her growing realisation of how others view her and her kind. She says:

“…there are people out there […] who don’t hate you or wish you any harm, but who nevertheless shudder at the very thought of you – of how you were brought into this world and why – and who dread the idea of your hand brushing against theirs.”

The character goes on:

“The first time you glimpse yourself through the eyes of a person like that, it’s a cold moment. It’s like walking past a mirror you’ve walked past every day of your life, and suddenly it shows you something else, something troubling and strange.”

To realise there are swathes of the world’s population who merely tolerate you is hard to accept at first. In Never Let me Go, Kathy learns to accept it. Her friend Ruth, a fellow clone, finds it harder. They both die anyway.

Accepting Ambivalence

There will always be people who have a private aversion to your existence – for believing in the wrong God (or Gods), and thus condemning yourself to purgatory or hell; for behaving outside the acceptable norms of your gender, or conversely, for slavishly adhering to them; for belonging to a nation that offers no freedom, however that freedom is defined; for having no money, or for having money and believing it will provide fulfilment. And so on.

Knowing we’re all, to varying degrees, objects of mild distaste, the idea that we’re tolerated becomes more attractive. We can be thankful there are people who will defend us and promote our rights, despite how alien we are to them.

The desire to have more than that can, suddenly and strangely, appear overambitious, and verging on vain.

Leave a comment