fiction

-

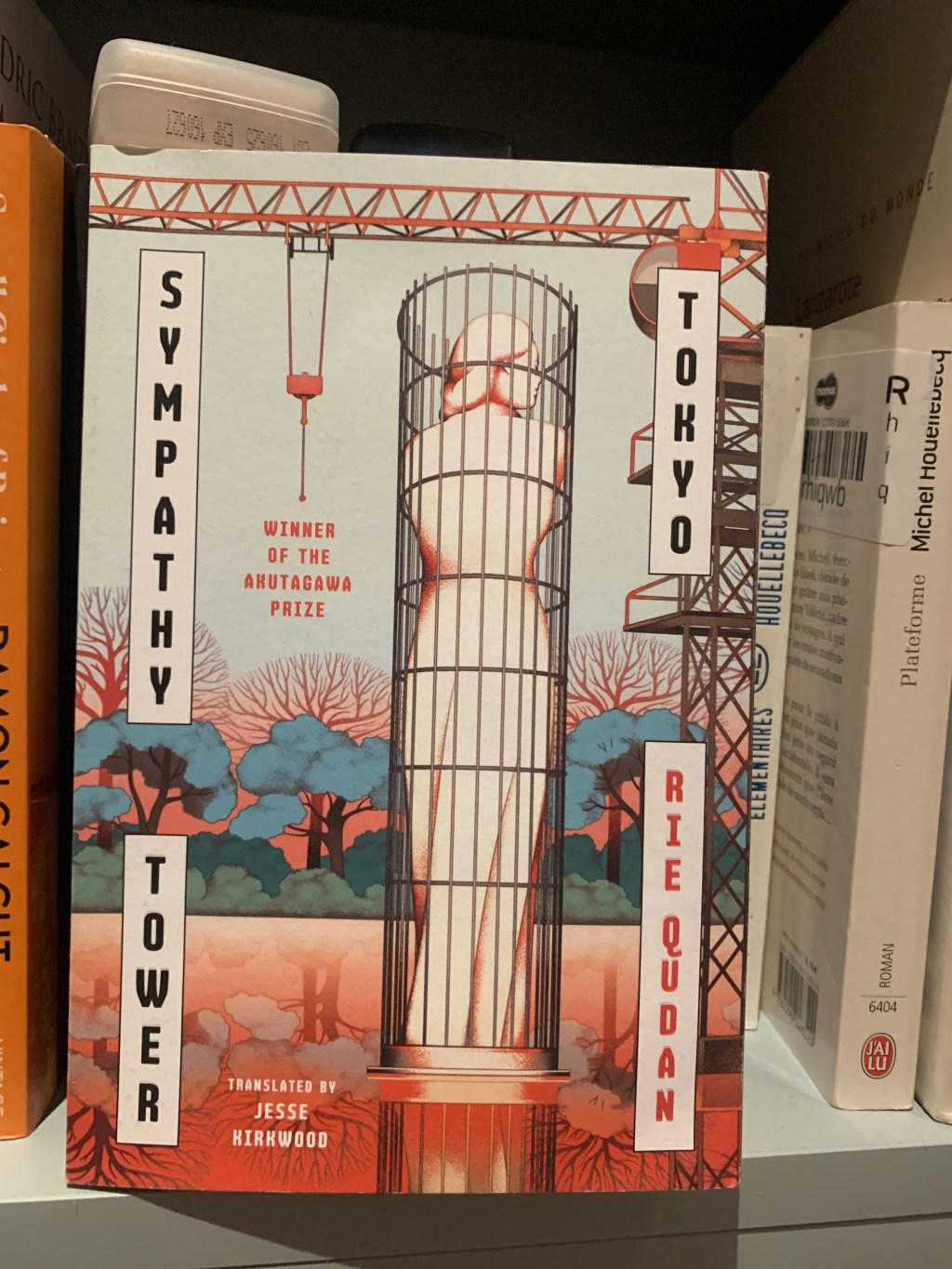

Which words won’t be OK in the future? And what will be the legacy of the work we do today? Rie Qudan poses these questions in her novel Sympathy Tower Tokyo, which came out in English this year, translated by Jesse Kirkwood. It made international headlines because Qudan shared that 5% of the novel was

-

I think most people, given the choice, would prefer to have their lives celebrated, rather than tolerated. “The way you live is fantastic” sounds more validating than “I respect your right to exist”, though I’m happy enough with the latter. Perhaps I have low expectations of others. There’s a minor episode in British politics relating

-

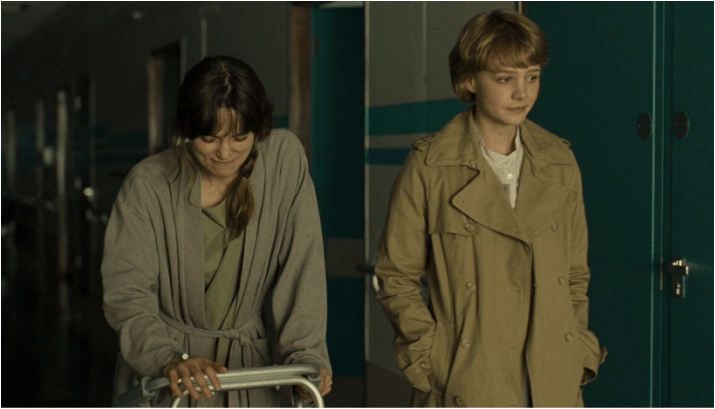

Bearing in mind he’s a cannibalistic serial killer, why is the character of Hannibal Lecter in the film adaptation of ‘Silence of the Lambs’ (based on Thomas Harris’s novel of the same name) not only compelling, but also likeable? More generally, what can portrayals of fictional characters tell us about the real world? Commentators cite

-

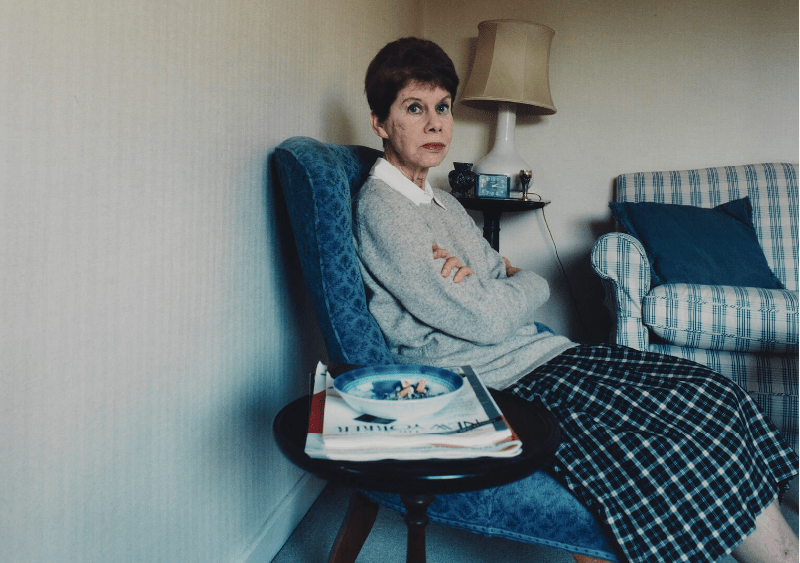

“People feel at home with low moral standards.” That’s a quotation from Hotel du Lac, a 1984 novel by Anita Brookner, an author whose works feature kind and gentle protagonists losing out on life’s prizes to bolder and more morally questionable characters. Thematically, her writing is like Kazuo Ishiguro’s in that it portrays characters who

-

When things go wrong, I assign primary blame to myself or to others. Whichever I choose, I have an object for my frustration. Blaming myself, I can self-motivate to create conditions for future success. Blaming others, I can strategise their comeuppance. There’s even comfort in distributing blame and doing nothing about it. “I could have